I have three stories to tell, and will try to keep this somewhat short.

I spent over seventeen years as a substitute teacher in the local high schools. I made no secret that I was a pastor, and found that this knowledge often sparked conversations with students. One day, a student approached me after class and stated “I’m an atheist.” Before I could respond, he yelled, “I hate you. All Christians are intolerant so I hate you.” He then ran from the classroom as though he expected some horrendous explosion from me. Had he stayed around, he would have heard me ask him why he thought as he did. After all, this was not the first time a student had shared their disagreement with my beliefs. I have had the opportunity to discuss such matters with Wiccans, Buddhists, Muslims, and others. ( And yes, such conversations are allowed in the public schools.)

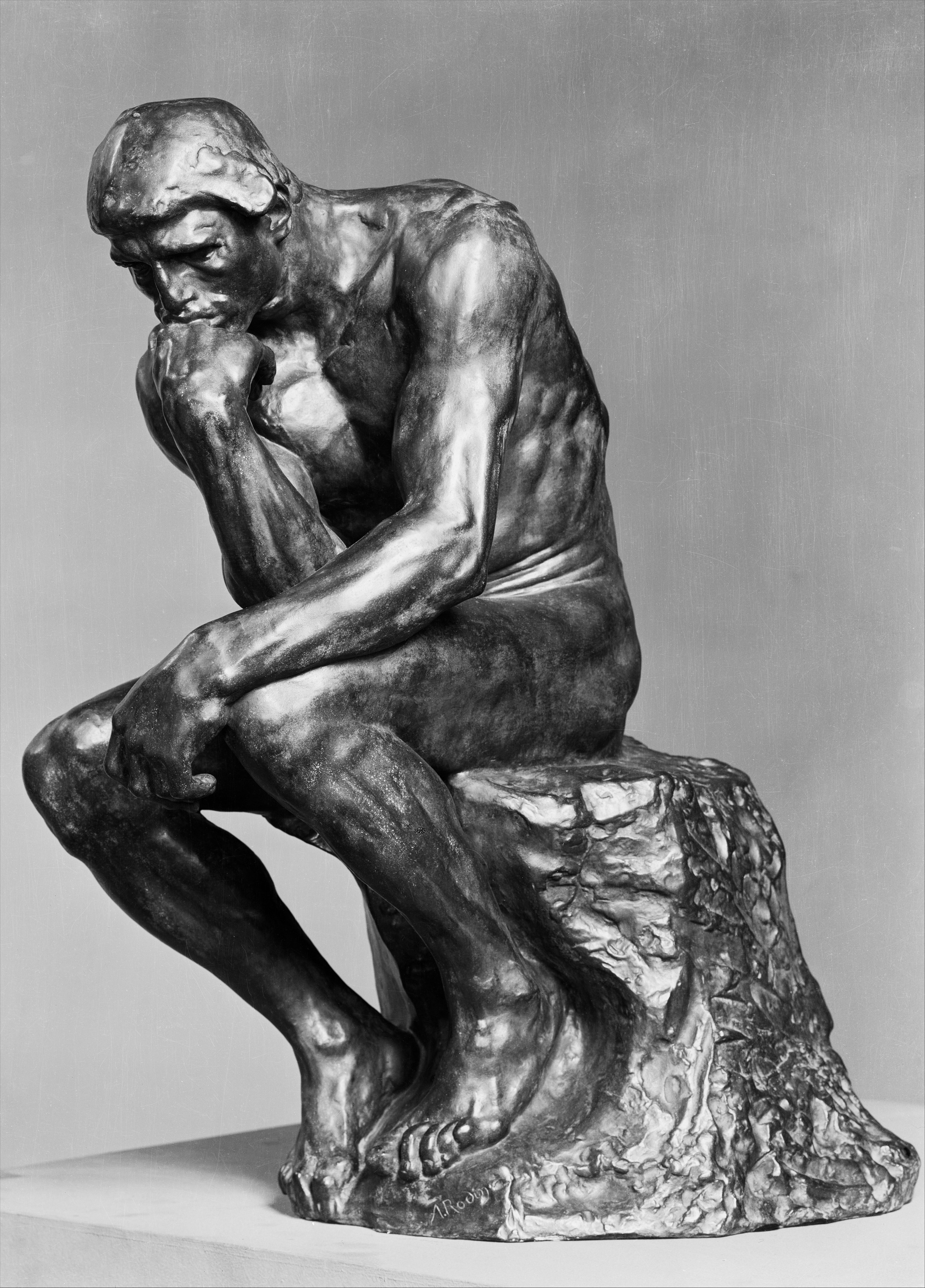

Which brings me to my second story. Jesus was having a discussion with an expert in religion. The expert asked Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. After some back and forth, the man stated that the law required him to love both God and his neighbor. Trying to be lawyerly, the man asked “who is my neighbor!” This was an important question because then he would know who he HAD to love, and who he could ignore or even hate.

Jesus then launched into what we know as the parable of the Good Samaritan. The set-up was that a Jewish man had been robbed and left for dead by bandits. Two religious Jewish leaders passed the man by, as he would be a hindrance to them. Only a Samaritan man picked the man up, tended his wounds, set him up in a lodge, and paid for his accommodations.

Like many stories told by Jesus, this often lacks context in our modern telling. The reality is that Samaritans and Jews really hated each other. The Jews saw the Samaritans as “half-breeds.” Think of the war and the hatred that some “full blood wizards” for those who were not, in Harry Potter, and you have some idea of the hatred involved. The Jews would not allow the Samaritans to help in the construction of the new temple, chased them out of Jerusalem, and burned down the Samaritan temple. They even fought on opposite sides during a Greek occupation.

So when Jesus stated in this story that even the hated Samaritans were to be seen as neighbors, his audience would have been shocked and even angry. No way! Besides, neighbor was universally seen as 1) family, 2) clan, and 3) tribe or nation. Anyone outside this setting could not be considered a neighbor, much less someone to be loved. That Jesus would even consider a Samaritan as worthy of love was a radical idea both in that time, as well as this.

This leads me to the third story. Two weeks before I sat down to write this, a man in New Zealand went into two mosques, opened fire, and killed fifty Muslims while at Friday prayers. This man can clearly be called a sociopath. What he did was a crime not only against these Muslims, but against God as well.

There are those who might think that I and other Christians would rejoice that our “enemies” were harmed. That all Christians and any who disagree with them are in a perpetual war, with each side espousing hatred. Supposedly, you are either a hater, or you must agree that ALL religions are equally true, and there is not “A” truth.

Both statements are false. I do not hate my Muslim neighbors. I have actually had several Muslim friends, including my wife’s former boss. I found mutual respect and even admiration between myself and these friends. On a number of occasions, my friends tried to share with me why I should convert to their religion. This was not hatred, it was shared in love, as they wanted me to know God (or Allah) as they did. I, in return, shared my faith as well, also out of love. There was no shouting, anger, or hostility, only love and concern for my supposedly “Samaritan” neighbors, and they for me.

This is what the murderer, the religious leader, and the student don’t get. That we can have differences, even strikingly strong differences, and still love one another. This is true tolerance. I am a strongly committed Christian. I have equally strong differences with other faiths, including Muslims. Yet I don’t love just my “tribe” of other Christians. My faith in Jesus makes me see ALL others as people created by God, deserving of my love and, if needed, my forgiveness.

I cry at the thought that fifty of my fellow human beings were murdered. I hate true intolerance, and fight against it. I love people wherever they are religiously, politically, racially, or nationally. After all, as Jesus showed, ALL are my neighbors, therefore they all need and deserve my love. Even today, this stands out as a most radical thought. Until next time.